GETTING READY FOR THE UNITARY PATENT SYSTEM

The European Unitary Patent System will soon enter into force. In this white paper, we refer to the 4 decisions you need to make as regards the Unitary Patent System.

Widenmayerstraße 10

Widenmayerstraße 10

80538 Munich

Find Us on Google Maps

Tel.: +49 89 41112880

The European Unitary Patent System will soon enter into force. In this white paper, we refer to the 4 decisions you need to make as regards the Unitary Patent System.

In recent years, the presence of quantum technologies in public media has increased, reaching a new high with Google’s announcement of “Quantum Supremacy” [1], which was covered by media all over the world. This shows that quantum technologies are in the process of transforming from a highly-specialized academic field of (fundamental) research to new technological applications.

The increasing interest in quantum technologies is also evident in a plurality of government-funded initiatives, including the European Quantum Flagship for quantum technologies [2], UK National Quantum Technologies Programme [3] and the US National Quantum Initiative [4], to name a few. Also, the German government launched a Federal Government Framework Programme called “Quantum technologies: from basic research to market” [5] for boosting the development of quantum technologies in Germany.

Additionally, established companies such as Google, Microsoft, D-Wave Systems, or IBM invest in their own research in the field of quantum technologies. At the same time, numerous start-ups are starting to explore the commercialisation of quantum technologies and successfully attract an increasing amount of private funding through venture capitalists [6].

The rise of quantum technologies is also evidenced in patent statistics, which generally provide a valuable source for studying and predicting changes and trends in technology. In the last decade, a number of reviews concerning patent statistics in the field of quantum technology have been published, for example by the UK Intellectual Property Office [7,8], the European Patent Office [9] and the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission [10].

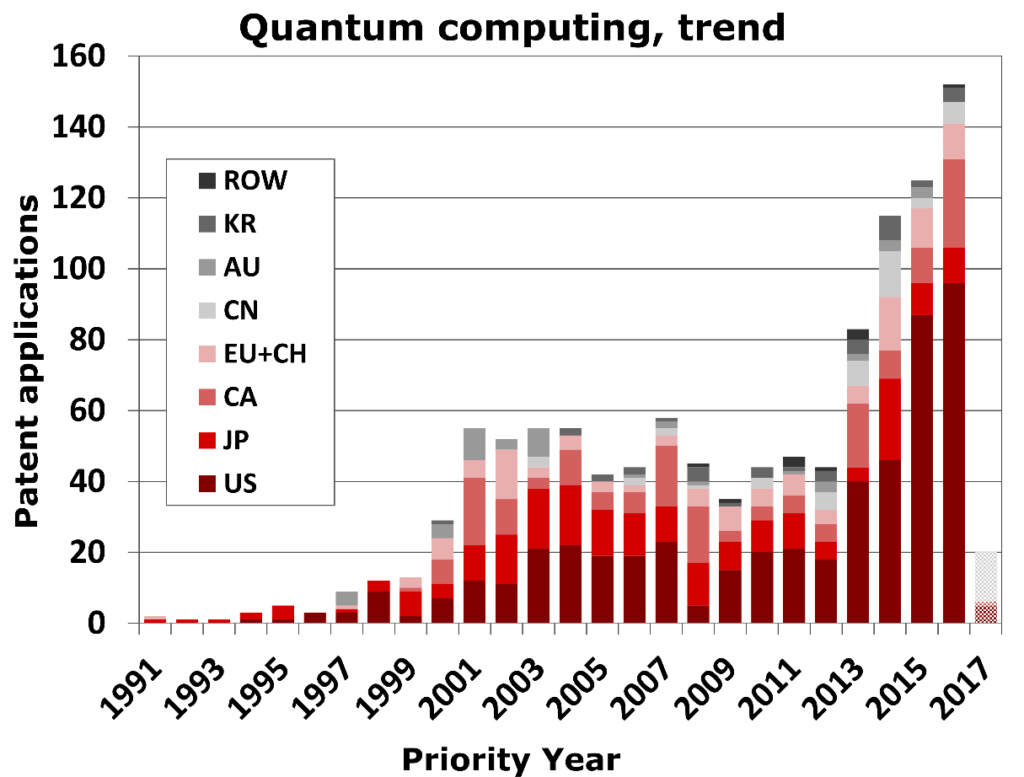

Generally, patent statistics show an increase of quantum technology-related applications within the last decade. For example, the below Figure depicts the number of patent applications related to the field of quantum computing per year, wherein the applications have been assigned to the country of the headquarters of the respective applicant (adapted from JRC report [10]). The data shows that after a first growth of patent applications in the 90s, the number of patent applications plateaued at around 50 per year for more than a decade. However, since 2013, there has been a steep increase leading to a tripling of the number of applications in about 4 years. Since the data were gathered in July and August of 2018, the numbers for 2017 are only preliminary and affected by the typical 18-months delay in publication of patent applications.

Figure: Number of patent applications on quantum computing per year, according to the country where the headquarters of the applicant is based (bar for 2017 shaded to indicate provisional results due to the typical 18-months delay period between filing and publication of patent applications), adapted from JRC report [10].

Overall, the data further shows that the main countries and regions where filing entities are based are the US, Japan, Canada and Europe, followed by China, Australia and South Korea, while the rest of the world (ROW) only plays a negligible role.

While the role of China in quantum computing appears to be limited, it is clearly leading in the field of quantum key distribution, where the number of patents filed by entities headquartered in China is vastly growing, and the cumulative number of patent applications already equals the patent applications filed in the following top counties, US and Japan, together (see [10]).

The introduction of the first commercial quantum-technology-based products to the market and the rising number of patent applications in the related field over the last decade show that quantum technologies are edging ever closer to assuming a major role for the technology of tomorrow. However, with the number of applications still being in the lower thousands, there still appears to be a lot of potential for further, new inventions and we are excited about the developments to come.

If you are interested in patenting your own inventions, for example in the field of quantum technologies, we are always happy to advise you regarding the possibilities of protecting your ideas, such as with a patent or utility model. With our diverse team coming from all kinds of backgrounds, including quantum technologies, we are certain that we can help you with your specific invention. You can reach us via email at mail@stellbrink-partner.com or by calling +49 89 41112880.

References

[1] https://blog.google/perspectives/sundar-pichai/what-our-quantum-computing-milestone-means

[5] https://www.bmbf.de/upload_filestore/pub/Quantum_technologies.pdf

You have made an outstanding invention and want to protect it, in particular in Europe, but you have already published it? The below article informs you about a grace period applying in Germany, which may still allow you to get protection for your invention in Germany.

One essential criterion for the patentability of an invention is novelty. According to patent law, an invention is considered novel if it does not form part of the state of the art defined by information publicly available before the filing date (or the priority date) of the patent application. This includes publications, other patents, presentations, fairs, company tours, the actual use of an invention in public, etc. In other words, an invention is considered to be public whenever an unlimited number of people could potentially gain knowledge about the invention. This may already be true if the invention is disclosed to a person which is not subject to secrecy. In particular, this also means that the development cannot be made public by the inventor themselves before the first filing date of the patent application.

But is there a way to obtain a patent even after an invention is made public? In some countries (e.g., in the US) there exist a so-called grace period, typically between 6 and 12 months, within which an invention may still be protected after its publication. However, the German and European patent law do generally not provide such a grace period.

There is a first exception to this general rule: According to Art. 55 (2) of the European Patent Convention (EPC) and the corresponding Par. 3 (5) No. 2 of the German Patent Law, there is a 6-months grace period, which applies to all publications happening as a consequence of the applicant publishing the invention at some defined international trade fairs (e.g., typically the “world fair”). However, according to our professional experience, this provision is of only of limited practical relevance.

Yet, there is a possibility to protect inventions at least in Germany even after they have been made available to the public: The German utility model. It is another form of an intellectual property right for protecting inventions. Further (and notably), it allows for a grace period of six months.

Generally, the criteria for a German utility model are the same as for a patent. That is, for a valid protection, the invention needs to be novel, involve an inventive step and be susceptible of industrial application. The main differences to a patent are that the application is not examined regarding the fulfilment of the required criteria and that the utility model cannot protect any process. Further, the term of the German utility model is only a maximum of 10 years compared to up to 20 years for a patent.

However, any description or use made within six months prior to the date of filing the application (or the priority date) is not considered prior art, if it is based on the elaboration of the applicant. That is, with regard to the own disclosures of the applicant (or their predecessor in title), there is a grace period of 6 months. In addition to that, a public prior use is only relevant when it happened in Germany.

Further, a German utility model can also be derived (or “split off”) from any pending patent application having effect in Germany, i.e., from any German, European or PCT application (for the latter two, only if Germany is designated). More precisely, splitting off the utility model can be done within 2 months after the end of the month in which the pendency of the application terminated (e.g., if the application forming the basis for the utility model is deemed to be withdrawn on January 03rd, the utility model can be derived by March 31st). Such a derived utility model enjoys the filing date and the priority date of the application on which it is based.

In summary, it is possible to gain protection for an invention in Germany even if the inventor has made it public, as long as an application is filed within 6 months after the publication, and a utility model based on this application is filed within the relevant time frames. Examples include that just the utility model is filed within 6 months from the publication, another patent application is filed within this time and the utility claims its priority, or a utility model can be derived from such an application. Besides the grace period, utility models also have the advantage of lower costs and a registration procedure of only several months. However, there is also a greater risk that it will be attacked and potentially being invalidated due to the lack of substantive examination prior to registration.

In any case, the utility model provide you with an opportunity of obtaining protection for your invention in Germany (and thus, in the largest market in Europe) even if you have published it.

Please do not hesitate to contact us in case of further questions regarding the discussed matter or if you would like advice regarding a specific invention. Please also let us know in case you know of any other jurisdictions in Europe where a corresponding grace period applies. You can reach us via email to mail@stellbrink-partner.com or by calling +49-89-41112880. We are always happy to help you!

We are very happy to announce that our team grew by five new members over the last few months.

Back in August 2018, Jennifer Toporowicz started her training as a patent paralegal with us. She is supporting our clients and our team in formal matters and official proceedings.

In October 2018, Shweta Agarwal and Diana Jaber joined the team. Diana is handling administrative matters and office organisation. Shweta started her training as a European patent attorney with us. Before joining our firm, she obtained her Master’s in Astronomy and Astrophysics from the University of Manchester, and worked at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics.

In December 2018, we welcomed Lukas Huthmacher and Richard Schild to our team. Both of them will train as German and European patent attorneys at our firm. Richard completed his joint Master’s in Mechanical Engineering at the Karlsruhe Institute for Technology and Arts et Métiers ParisTech, and worked for a startup before joining us. Lukas studied physics at the ETH Zurich and recently obtained his PhD in physics from the University of Cambridge.

We are very happy that we were able to fill all of our job openings last year with excellent candidates, and thus provide our services to a constantly growing client base.

In Germany, there are approximately 4 ,400 patent attorneys. Approximately 1 ,600 of those are based in Munich. That is, approximately every third German patent attorney works in Munich. In this article, we would like to shed some light on the reasons for that.

The first likely reason is the large presence of very good technical universities in Munich. To qualify as a German patent attorney, one needs to hold an academic degree in natural sciences or engineering. Munich is home to the Technical University and the Ludwig Maximilian University. These universities have an outstanding reputation for engineering and natural sciences, both nationally in Germany as well as internationally. Thus, there are many candidates in Munich who could potentially qualify as patent attorneys.

In addition, many large companies with a technical focus are based in Munich or in Munich’s vicinity, e.g., BMW, Siemens, and Infineon. These companies do not only employ many patent attorneys, but also engage external patent attorneys for some additional tasks.

Further, and probably most importantly, the European Patent Office, the German Patent and Trademark Office, and the German Federal Patent Court are all based in Munich. The patent offices examine European and German patent applications, respectively, and the Federal Patent Court reviews decisions of the German Patent and Trademark Office. Patent attorneys often need to visit these offices and this court, e.g., for oral proceedings. A home base in Munich is therefore useful be close to these institutions, and to spare the clients costs for travelling and accommodation. Further, the patent offices and the patent court create an excellent “ecosystem” in Munich: Munich is home to numerous patent examiners, patent judges, and patent attorneys. This enormously facilitates the professional exchange, both at conferences and at an informal level.

Due to all these reasons, Munich is a very suitable base for patent attorneys, which is also why we decided to establish our practice in Munich.

Do you have any questions relating to patent law? If so, please feel free to contact us by calling +49-89-41112880 or via email to mail@stellbrink-partner.com. In case you are interested in qualifying as a patent attorney, or in case you are generally interested in working for our firm, please feel free to contact us by calling the above number or via email to careers@stellbrink-partner.com. We are looking forward to hearing from you!

On April 26th, the United Kingdom became the 16th nation to ratify the Unitary Patent Court agreement, bringing the Unitary Patent closer to reality. Once in force, the agreement will make it possible to enforce IP rights across all countries that have ratified the agreement via a single court. With its implementation, the UPC agreement will bring forth closer European integration as regards patent litigation.

As our readers may recall, to enter into force, the UPC must be ratified by at least 13 nations, as well as all three of Germany, France and the UK (as the three nations with the largest number of active European patents). After Brexit, all eyes have been on the UK, as the UPC agreement was suddenly up in the air again. With the ratification by the UK, the last obstacle on the path to a Unitary Patent remains a German constitutional court challenge to the agreement, still pending at this date. The pressure is now on, and many heads will turn toward Germany with the hope and expectation to resolve the challenge quickly.

In recent years, we have advised numerous founders and startups, and we have been able to repeatedly witness how clever technical ideas created companies with more than a hundred employees. We are pleased and proud to be able to contribute to our clients’ success.

We have realized that at the beginning of the patenting process, founders and startups always ask themselves similar questions that we would like to answer here.

What is the difference between patents, trademarks and designs?

Basically, these are very different protection rights, which grant very different protections.

Patents are technical IP rights by which technical teachings can be protected. For instance, a new technology in a robot or a technically new process. The airbag of a car can serve as a concise example: Here, a problem (protection of occupants in case of an accident) is solved by technical means (rapid inflation of an air cushion).

As a trademark, one can protect everything (more precisely: all “signs”), which can identify products or services of a particular source. These are, above all, words (for example “Apple”) and pictures (for example the Apple logo) as well as combinations thereof. Although there are other types of trademarks (for example, color trademarks), these are in practice much less common than the trademarks mentioned above, so we will not go into more detail here.

By means of a design you can protect the shape of a product. Certainly, a concise example of this is the iPhone. In addition to many patents that protect the technical functionality of this product, the shape as such is also protected.

A German utility model is also a technical property right that protects technical inventions and is often considered to be “the little brother” of patents. However, it differs from a patent in (1) that it is not tested and (2) that the utility model cannot protect any process.

At Stellbrink & Partner, we are currently focusing on technical property rights, i.e., patents and utility models, which is why the following questions relate to these ones. We are also happy to help you with questions about other property rights, since we also have the knowledge to answer most of your questions. In addition, we have a large network and can recommend specialists in the field in case of any special query.

What can I protect with patents?

As mentioned before, patents are technical property rights (at least in Europe). Therefore, patents can be used to protect technical solutions. This is always the case when using “natural forces” or engineering skills to solve a problem.

At first, it sounds pretentious, but in many cases, it is not. After all, you essentially need a (smart) idea that makes a product or process, compared to other products or processes, better (or just different). It covers patentable inventions from high technology areas (e.g. aerospace) to everyday objects – even a clothespin would be patentable (if it was not already known).

Pure business methods are not patentable – here the problems and the solutions are not technical, but purely in the field of economics/business.

In terms of patentability, computer-implemented inventions are of particular interest. In fact, they are so relevant that we have dedicated a separate section to them.

When founders or developers ask themselves if their development is patentable, the answer is, in most cases, “yes” – at least that is what our experience teaches us. Should you have any doubts or questions, we always advise you to contact a patent attorney who can tell you quickly and easily if your doubts are well founded.

Is it possible to protect software and computer-implemented inventions?

Nowadays, during the initial consultations, many questions concern software or computer-implemented inventions.

In Europe, it is regulated by law that a software as such is not patentable. Basically, this is to prevent that aspects for which no patent protection can be obtained (for example, a business method) become patentable solely by the fact that they are carried out on a computer (and thus by technical means). For this reason, software as such is not patentable. A pure business method performed on a computer cannot be patented in Europe.

However, there are software or computer-implemented inventions that are technical for other reasons.

For example, a computer algorithm that can analyze metrics quickly and less susceptible to errors, and in case of a crash, uses this to trigger an airbag faster. In this case, a technical problem is solved with the algorithm, in other words, by technical means, and therefore eligible for patent protection.

The concrete questions almost always take place between the extremes described above. Far too often, however, we hear of startups who were basically discouraged from filing a patent because they “only” invented a software. We are firmly convinced that this is not the full picture and you always have to deal with the specific case.

What are the requirements for patent protection?

In the above questions, we have been primarily concerned about whether a development is accessible to patent protection per se. This is, in the narrower sense of the word, the patentability. Since only technical developments are intrinsically patentable, this can also be called technicity.

However, there are additional requirements that must be met in order to obtain a patent.

An essential condition is novelty. In order to obtain an effective patent, the invention to be protected must be novel. This means that the invention was not made public before the date on which the patent application is filed. An invention is public whenever it is potentially accessible to an unlimited number of people. Examples of this may be publications in a patent or in a journal, but also presentations, sales, trade shows, company tours, etc. (which also depends on the circumstances of the individual case).

Regarding novelty, basically both your publications and all other publications are taken into account – including patents and other publications by third parties. As a general rule, disclosure to any person who is not subject to secrecy can present a publication. So, if you consider filing a patent application, it is important that you submit it before you report the invention to people who are not subject to secrecy.

However, there are some exceptions. Even if you have already published your invention, there is still a possibility, in some countries, of obtaining protection within a grace period (usually between 6 and 12 months depending on the country). If that is the case, you should seek immediate advice!

The above-mentioned novelty is given if your invention has not yet existed in this way. Your invention will therefore be compared with products and publications published before the date of your patent application, which are also known as prior art. If your invention is not yet included in the prior art, it is new.

Another requirement is that your invention is based on an inventive step. This is the case if your invention is not obvious. This requirement prevents ordinary developments from being protected by a patent. Patent protection should only be granted for developments that go beyond the normal skills of a professional. If, for example, a nail is replaced by a screw in a component, this is new in accordance with the above statements – this component has not yet existed in this form. However, such an exchange is (at least in most cases) within the ordinary skill of the art, so that such a development is obvious and therefore has no inventive step. The inventive step always requires a detailed examination on a case-by-case basis.

What are the chances of obtaining a patent?

In our experience, it is possible in most cases, to obtain a patent for an invention (as long as the very invention has not been revealed before registration). In our opinion, the crucial question is not so much whether to obtain a patent, but how broad the scope of protection afforded by the patent will be.

Let’s illustrate this with an example: In the past, we have had various patent litigation involving a wound treatment device. Briefly, it has been found that it may be advantageous to treat large wounds with an airtight foam dressing to which a negative pressure is applied. Such an invention (defined by “airtight foam dressing + negative pressure”) could be debatable as to whether it is based on an inventive step in view of airtight foam dressings and knowing that negative pressure wound drainage may be beneficial. But if you have other features that further distinguish this development (for example, a foam specially adapted to the vacuum foam dressing or a particularly suitable adhesive for attaching the dressing), it is much more likely to obtain a patent for such a combination.

In our experience, most new technological developments can be patented, but the question is how general or broad is the protection that you get.

What is the process until I get a patent?

The patenting process starts with the preparation of a patent application. Ideally, this happens in close coordination between the inventor and the patent attorney. The patent application outlines the state of the art of the invention, why this prior art is disadvantageous, and then explains the invention. The claims are of particular importance, since they indicate what protection is claimed. The preparation of the patent application usually takes several weeks to complete – in case of need (especially if a publication is imminent), a patent application can also be worked out in a much shorter time.

Such a patent application is then filed to the Patent Office, and assigned to search and examination. The Patent Office investigates and examines whether the conditions for a patent exist. In addition to some formal requirements, the Patent Office examines, above all, whether the invention is new and based on an inventive step.

If the Patent Office comes to the conclusion that the patent application as filed is not allowable, it will communicate this in an official letter and provide the opportunity to answer it. One may then answer with a letter bringing forward arguments and potentially amend the claims, which define the protection, to overcome objections that have been raised by the Patent Office.

The Patent Office will raise objections until it considers that the case is ready for a decision – granting of the patent or rejection.

The number of such letters of the Office raising objections before the procedure is completed can vary widely. From our experience, the average is about 2 to 3 of such letters. Every decision and every reply takes about half a year to be completed, which can also vary greatly, so that it has to be expected an average of about 2 to 3 years before getting a decision. In urgent cases, for example, if a competitor uses an invention, this procedure can also be accelerated.

Is a patent valid worldwide?

Basically, patents have the principle of territoriality, which means that every state can grant patents for its territory only. In other words, patents are generally national property rights and you must always submit your own application for each country in which you want to have patent protection.

But there are several rights and treaties in which several states have joined forces to simplify the patenting process.

First of all, a right of priority applies to the vast majority of countries. By means of thus, the applicant has the right to make further subsequent applications within one year. As long as they relate to the same invention as the first application, subsequent applications will be treated as having been filed on the date of the first application. This is particularly relevant to what is considered prior art and therefore plays a role in the assessment of novelty and inventive step. Therefore, if you file a patent application today, you will have one year to make further filings, and the state of the art – and especially your activities – published during this period will not be considered for these further filings.

Further, all European states (in addition to the EU states, also other states, such as Switzerland, Norway, and Turkey) have signed the so called European Patent Convention (EPC). By means of the EPC, one may have one unified patent examination proceeding for all the member states of the EPC. This makes it possible to obtain patents in all EPC countries through an application examined by the European Patent Office (based in Munich). If you want to have patent protection in several European countries, this can be much more efficient (and cheaper) than individual patenting processes in each country.

In the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), the vast majority of countries have joined forces to form a filing association. That means you can file an application for a large number of states and then decide later (within 2.5 years) in which states you want to continue your application.

What do I gain from a patent?

By law, a patent is a temporary exclusive right. A patent can be used to exclude third parties, in particular competitors, from using the patented invention – therefore, one “monopolizes” the invention. If a third party uses the invention, they can be forced to refrain from using it, if necessary in court.

Obviously, such a monopoly position represents a substantial competitive advantage and therefore contributes to the enterprise value – especially for small and young companies with a technological focus, such a patent (or the prospect) can constitute a substantial value for the company. Once again, we find that investors pay particular attention to a patent situation, especially with young companies, and regard patents and patent applications as a kind of security for their investment – after all, a patent also provides official confirmation that a technological development is new and inventive.

What are the costs of registering a patent?

There are basically two cost factors that arise in the patenting process. These are, on the one hand, the administrative fees charged by the patent offices and, on the other hand, the costs of appointing a patent attorney. Although the commissioning of a patent attorney is not mandatory (and you could also perform the patent granting without a patent attorney) – in practice, however, a patenting process implies so much special knowledge and pitfalls, that it always makes sense to ask for the assistance of a patent attorney.

The official fees depend essentially on the patent office, which charges for the search and the examination of the patent application. The German Patent and Trademark Office charges about € 500 in fees until the patent is granted, and the European Patent Office charges about € 4,000 of which approximately € 1.500 are incurred at the beginning of the search and the remaining in the following years.

The patent attorney’s fees depend primarily on the effort that your patent attorney is investing in the preparation of the application and further process. Most patent attorneys have an hourly rate ranging from € 250 to € 450. Often, lump sums are also agreed for the initial preparation of an application, which may be approximately in the range of € 3,000 to € 15,000. These prices are very difficult to compare and mostly reflect how much effort the patent attorney invests in the preparation of the application, which can lead to a varying degree of detail of the application.

Furthermore, one has to expect that until the completion of the examination process, further legal fees in the amount of several thousand euros are necessary – but this can vary greatly and depends on various factors, for example: how many answers to office actions are necessary and how complex they are. A very rough estimate here would be that the legal fees incurred in the course of the examination process are approximately € 5,000 (which can vary widely).

All in all, you roughly have to expect a investment of € 10,000 to € 20,000 in a patent grant procedure.

Does it make sense for me to apply for a patent?

Ultimately, this is an economic question that the inventor or entrepreneur can only answer for themselves. But we can give some help for this, which is based on our extended experience in this field.

As shown, a patent application represents a substantial investment. This is usually worthwhile only if there is a substantial economic interest involved. Our rule of thumb is: If you were now willing make a downpayment of € 100,000, so that your invention will not be used by anyone else, it is worth making a patent application. If you were now not willing to make a downpayment of € 20,000 for that, you have to question very carefully whether the investment makes sense – in between these two values, there is a certain gray area.

In evaluating this investment, there may also be other aspects playing a role alongside the legal advantage of exclusive rights – for example, the advertising effect of a patent and also the effect that a patent could have on potential investors.

All of these aspects should be considered in the decision-making process of whether a patent application makes sense for you.

Do you have more questions?

We hope that we have been able to answer your initial questions. Let us know if you have any further questions or would like advice on a specific invention! You can reach us at mail@stellbrink-partner.com or by phone at + 49-89-41112880.

We are happy to announce that Christian Fernández Solis joined our firm in December 2017.

Christian is a physical chemist and engineer with an international track record of excellence: he graduated top of his class in Industrial Chemistry in Asunción (Paraguay) and completed his Master of Engineering in Materials and Environmental Science at Nagoya University (Japan) before completing his doctoral degree at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum, and working at the Max-Planck-Institut für Eisenforschung in Düsseldorf.

Christian is a physical chemist and engineer with an international track record of excellence: he graduated top of his class in Industrial Chemistry in Asunción (Paraguay) and completed his Master of Engineering in Materials and Environmental Science at Nagoya University (Japan) before completing his doctoral degree at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum, and working at the Max-Planck-Institut für Eisenforschung in Düsseldorf.

Christian is fluent in 6 languages and further strengthens our expertise in the fields of chemistry and material sciences.

“We were thrilled to recruit Christian”, says Axel Stellbrink. “We know that Christian was invited for interviews in many patent law firms, but deliberately chose to join our firm. Only hiring the best individuals is a cornerstone of our strategy, and we are always happy when we see that we can attract these highly talented people.”

Welcome to the team, Christian!

In the recent past, standard-essential patents (SEP) and FRAND licenses have played an important role in many patent infringement proceedings. FRAND licenses are licenses that are fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory.

The basic rationale is the following: There are some patents protecting a technological standard, e.g., a patent that is essential for a mobile communication standard. That is, anyone using this mobile communication network has to make use of this patent. Such patents would grant the patentee a disproportional amount of power if the patentee could exclude any other party from using this patent. This is why the patentee is obliged to grant a FRAND license to any party willing to accept such a license. In particular, the patentee of a standard-essential patent cannot successfully assert a cease and desist claim in court if the other party is willing to accept a FRAND license.

The basic rationale is the following: There are some patents protecting a technological standard, e.g., a patent that is essential for a mobile communication standard. That is, anyone using this mobile communication network has to make use of this patent. Such patents would grant the patentee a disproportional amount of power if the patentee could exclude any other party from using this patent. This is why the patentee is obliged to grant a FRAND license to any party willing to accept such a license. In particular, the patentee of a standard-essential patent cannot successfully assert a cease and desist claim in court if the other party is willing to accept a FRAND license.

While the above illustrates the general idea, there have been numerous questions as to which obligations the patentee and the user of an SEP have to meet to fulfill their requirements relating to the FRAND license and to the licensing negotiations. For Germany, some of these questions have been answered by recent case law, some of which will be reviewed in this article.

One of the most fundamental decisions relating to SEP and FRAND was issued by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) with its judgement C-170/13 dated July 16th, 2015. The ruling concerned the circumstances under which the patentee of an SEP can assert cease and desist claims in court proceedings. As already stated, in general, the patentee is not allowed to do so if the alleged infringer is willing to take a license and does not delay the licensing negotiations.

In that regard, the patentee and the alleged infringer have to follow a certain procedure during the licensing negotiations.

1. Before asserting the cease and desist claim in court proceedings, the patentee has to inform the alleged infringer of the patent claim (patentee informing alleged infringer).

2. The alleged infringer then has to request a license under FRAND conditions within a short time (FRAND request).

3. In turn, the patentee has to make a FRAND offer including details as regards the royalty rate and its calculation (FRAND offer). A recent decision by the Higher District Court Düsseldorf also states that the patentee has to substantiate how the asserted patents are infringed. This includes references to the respective standard and claim charts (see OLG Düsseldorf, I-15 U 66-15, decision of 17. November 2016).

4. a) The alleged infringer can either accept the FRAND offer (FRAND acceptance) OR

4. b) The alleged infringer can make a counter offer complying with FRAND conditions (FRAND counter offer).

If this is the case, and the patentee does not accept the counter offer, the alleged infringer has to render account for the usage of the patent and furnish a respective security.

If the alleged infringer complies with their duties (including a FRAND request in due time and a FRAND acceptance or counter offer), the patentee cannot assert the cease and desist claims in court.

The above considerations (and further considerations on the exact case and more specific case law) will have to be taken into account by anyone wanting to assert a SEP and by anyone being attacked with a SEP.

![]() Of course, the above is just a very short summary of some of the recent decisions relating to SEP and FRAND licenses in Germany, and that many others exist, providing further details on individual questions. However, mentioning all of them would render this article too complex, as it is only intended to provide an introduction and a high-level summary. It is generally noted that this article can never replace individual legal counselling. If you have any question relating to SEP and/or FRAND licenses, please feel free to contact us at mail@stellbrink-partner.com. We are always happy to help you.

Of course, the above is just a very short summary of some of the recent decisions relating to SEP and FRAND licenses in Germany, and that many others exist, providing further details on individual questions. However, mentioning all of them would render this article too complex, as it is only intended to provide an introduction and a high-level summary. It is generally noted that this article can never replace individual legal counselling. If you have any question relating to SEP and/or FRAND licenses, please feel free to contact us at mail@stellbrink-partner.com. We are always happy to help you.

The unitary patent has been in the works for a number of years. The basic idea is simple: allow for a central system of patent litigation for patents in Europe (as opposed to litigation being tied to each of the individual countries where a European patent is validated). Based on the agreed rules, a new court would be established having a central division in Paris, London, and Munich.

The unitary patent has been in the works for a number of years. The basic idea is simple: allow for a central system of patent litigation for patents in Europe (as opposed to litigation being tied to each of the individual countries where a European patent is validated). Based on the agreed rules, a new court would be established having a central division in Paris, London, and Munich.

For the unitary patent to come into effect, France, the UK and Germany must ratify the agreement. France has done so in 2014 already. Ratification by the UK has been called into question after the Brexit vote, but since then there have been statements by the members of the UK government indicating that they are still open to ratifying the agreement. On June 13th, a new obstacle to the implementation of the unitary patent emerged. Germany, which was well on course to ratifying the agreement, put a halt to it in view of a complaint from an unnamed individual insinuating that the ratification would violate German law. The German constitutional court in Karlsruhe put the ratification process on hold while it investigates the complaint.

Although accelerated proceedings are expected, the process is likely to further delay the implementation of the unitary patent and the start of operation of the Unified Patent Court. It now seems more and more unlikely that the courts can start reviewing their first cases in December 2017, as originally planned. With further delay of German ratification, the UK’s Brexit negotiations can also further affect the start of the unified court’s operations. We will keep you updated on any further developments in the long and difficult story of the unitary patent.