Patent, Trademark or Design? How to find the right protection

In recent years, we have advised numerous founders and startups, and we have been able to repeatedly witness how clever technical ideas created companies with more than a hundred employees. We are pleased and proud to be able to contribute to our clients’ success.

We have realized that at the beginning of the patenting process, founders and startups always ask themselves similar questions that we would like to answer here.

What is the difference between patents, trademarks and designs?

Basically, these are very different protection rights, which grant very different protections.

Patents are technical IP rights by which technical teachings can be protected. For instance, a new technology in a robot or a technically new process. The airbag of a car can serve as a concise example: Here, a problem (protection of occupants in case of an accident) is solved by technical means (rapid inflation of an air cushion).

As a trademark, one can protect everything (more precisely: all “signs”), which can identify products or services of a particular source. These are, above all, words (for example “Apple”) and pictures (for example the Apple logo) as well as combinations thereof. Although there are other types of trademarks (for example, color trademarks), these are in practice much less common than the trademarks mentioned above, so we will not go into more detail here.

By means of a design you can protect the shape of a product. Certainly, a concise example of this is the iPhone. In addition to many patents that protect the technical functionality of this product, the shape as such is also protected.

A German utility model is also a technical property right that protects technical inventions and is often considered to be “the little brother” of patents. However, it differs from a patent in (1) that it is not tested and (2) that the utility model cannot protect any process.

At Stellbrink & Partner, we are currently focusing on technical property rights, i.e., patents and utility models, which is why the following questions relate to these ones. We are also happy to help you with questions about other property rights, since we also have the knowledge to answer most of your questions. In addition, we have a large network and can recommend specialists in the field in case of any special query.

What can I protect with patents?

As mentioned before, patents are technical property rights (at least in Europe). Therefore, patents can be used to protect technical solutions. This is always the case when using “natural forces” or engineering skills to solve a problem.

At first, it sounds pretentious, but in many cases, it is not. After all, you essentially need a (smart) idea that makes a product or process, compared to other products or processes, better (or just different). It covers patentable inventions from high technology areas (e.g. aerospace) to everyday objects – even a clothespin would be patentable (if it was not already known).

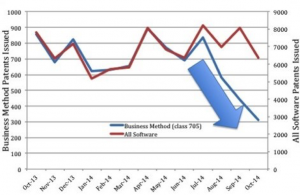

Pure business methods are not patentable – here the problems and the solutions are not technical, but purely in the field of economics/business.

In terms of patentability, computer-implemented inventions are of particular interest. In fact, they are so relevant that we have dedicated a separate section to them.

When founders or developers ask themselves if their development is patentable, the answer is, in most cases, “yes” – at least that is what our experience teaches us. Should you have any doubts or questions, we always advise you to contact a patent attorney who can tell you quickly and easily if your doubts are well founded.

Is it possible to protect software and computer-implemented inventions?

Nowadays, during the initial consultations, many questions concern software or computer-implemented inventions.

In Europe, it is regulated by law that a software as such is not patentable. Basically, this is to prevent that aspects for which no patent protection can be obtained (for example, a business method) become patentable solely by the fact that they are carried out on a computer (and thus by technical means). For this reason, software as such is not patentable. A pure business method performed on a computer cannot be patented in Europe.

However, there are software or computer-implemented inventions that are technical for other reasons.

For example, a computer algorithm that can analyze metrics quickly and less susceptible to errors, and in case of a crash, uses this to trigger an airbag faster. In this case, a technical problem is solved with the algorithm, in other words, by technical means, and therefore eligible for patent protection.

The concrete questions almost always take place between the extremes described above. Far too often, however, we hear of startups who were basically discouraged from filing a patent because they “only” invented a software. We are firmly convinced that this is not the full picture and you always have to deal with the specific case.

What are the requirements for patent protection?

In the above questions, we have been primarily concerned about whether a development is accessible to patent protection per se. This is, in the narrower sense of the word, the patentability. Since only technical developments are intrinsically patentable, this can also be called technicity.

However, there are additional requirements that must be met in order to obtain a patent.

An essential condition is novelty. In order to obtain an effective patent, the invention to be protected must be novel. This means that the invention was not made public before the date on which the patent application is filed. An invention is public whenever it is potentially accessible to an unlimited number of people. Examples of this may be publications in a patent or in a journal, but also presentations, sales, trade shows, company tours, etc. (which also depends on the circumstances of the individual case).

Regarding novelty, basically both your publications and all other publications are taken into account – including patents and other publications by third parties. As a general rule, disclosure to any person who is not subject to secrecy can present a publication. So, if you consider filing a patent application, it is important that you submit it before you report the invention to people who are not subject to secrecy.

However, there are some exceptions. Even if you have already published your invention, there is still a possibility, in some countries, of obtaining protection within a grace period (usually between 6 and 12 months depending on the country). If that is the case, you should seek immediate advice!

The above-mentioned novelty is given if your invention has not yet existed in this way. Your invention will therefore be compared with products and publications published before the date of your patent application, which are also known as prior art. If your invention is not yet included in the prior art, it is new.

Another requirement is that your invention is based on an inventive step. This is the case if your invention is not obvious. This requirement prevents ordinary developments from being protected by a patent. Patent protection should only be granted for developments that go beyond the normal skills of a professional. If, for example, a nail is replaced by a screw in a component, this is new in accordance with the above statements – this component has not yet existed in this form. However, such an exchange is (at least in most cases) within the ordinary skill of the art, so that such a development is obvious and therefore has no inventive step. The inventive step always requires a detailed examination on a case-by-case basis.

What are the chances of obtaining a patent?

In our experience, it is possible in most cases, to obtain a patent for an invention (as long as the very invention has not been revealed before registration). In our opinion, the crucial question is not so much whether to obtain a patent, but how broad the scope of protection afforded by the patent will be.

Let’s illustrate this with an example: In the past, we have had various patent litigation involving a wound treatment device. Briefly, it has been found that it may be advantageous to treat large wounds with an airtight foam dressing to which a negative pressure is applied. Such an invention (defined by “airtight foam dressing + negative pressure”) could be debatable as to whether it is based on an inventive step in view of airtight foam dressings and knowing that negative pressure wound drainage may be beneficial. But if you have other features that further distinguish this development (for example, a foam specially adapted to the vacuum foam dressing or a particularly suitable adhesive for attaching the dressing), it is much more likely to obtain a patent for such a combination.

In our experience, most new technological developments can be patented, but the question is how general or broad is the protection that you get.

What is the process until I get a patent?

The patenting process starts with the preparation of a patent application. Ideally, this happens in close coordination between the inventor and the patent attorney. The patent application outlines the state of the art of the invention, why this prior art is disadvantageous, and then explains the invention. The claims are of particular importance, since they indicate what protection is claimed. The preparation of the patent application usually takes several weeks to complete – in case of need (especially if a publication is imminent), a patent application can also be worked out in a much shorter time.

Such a patent application is then filed to the Patent Office, and assigned to search and examination. The Patent Office investigates and examines whether the conditions for a patent exist. In addition to some formal requirements, the Patent Office examines, above all, whether the invention is new and based on an inventive step.

If the Patent Office comes to the conclusion that the patent application as filed is not allowable, it will communicate this in an official letter and provide the opportunity to answer it. One may then answer with a letter bringing forward arguments and potentially amend the claims, which define the protection, to overcome objections that have been raised by the Patent Office.

The Patent Office will raise objections until it considers that the case is ready for a decision – granting of the patent or rejection.

The number of such letters of the Office raising objections before the procedure is completed can vary widely. From our experience, the average is about 2 to 3 of such letters. Every decision and every reply takes about half a year to be completed, which can also vary greatly, so that it has to be expected an average of about 2 to 3 years before getting a decision. In urgent cases, for example, if a competitor uses an invention, this procedure can also be accelerated.

Is a patent valid worldwide?

Basically, patents have the principle of territoriality, which means that every state can grant patents for its territory only. In other words, patents are generally national property rights and you must always submit your own application for each country in which you want to have patent protection.

But there are several rights and treaties in which several states have joined forces to simplify the patenting process.

First of all, a right of priority applies to the vast majority of countries. By means of thus, the applicant has the right to make further subsequent applications within one year. As long as they relate to the same invention as the first application, subsequent applications will be treated as having been filed on the date of the first application. This is particularly relevant to what is considered prior art and therefore plays a role in the assessment of novelty and inventive step. Therefore, if you file a patent application today, you will have one year to make further filings, and the state of the art – and especially your activities – published during this period will not be considered for these further filings.

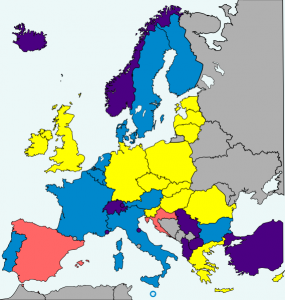

Further, all European states (in addition to the EU states, also other states, such as Switzerland, Norway, and Turkey) have signed the so called European Patent Convention (EPC). By means of the EPC, one may have one unified patent examination proceeding for all the member states of the EPC. This makes it possible to obtain patents in all EPC countries through an application examined by the European Patent Office (based in Munich). If you want to have patent protection in several European countries, this can be much more efficient (and cheaper) than individual patenting processes in each country.

In the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), the vast majority of countries have joined forces to form a filing association. That means you can file an application for a large number of states and then decide later (within 2.5 years) in which states you want to continue your application.

What do I gain from a patent?

By law, a patent is a temporary exclusive right. A patent can be used to exclude third parties, in particular competitors, from using the patented invention – therefore, one “monopolizes” the invention. If a third party uses the invention, they can be forced to refrain from using it, if necessary in court.

Obviously, such a monopoly position represents a substantial competitive advantage and therefore contributes to the enterprise value – especially for small and young companies with a technological focus, such a patent (or the prospect) can constitute a substantial value for the company. Once again, we find that investors pay particular attention to a patent situation, especially with young companies, and regard patents and patent applications as a kind of security for their investment – after all, a patent also provides official confirmation that a technological development is new and inventive.

What are the costs of registering a patent?

There are basically two cost factors that arise in the patenting process. These are, on the one hand, the administrative fees charged by the patent offices and, on the other hand, the costs of appointing a patent attorney. Although the commissioning of a patent attorney is not mandatory (and you could also perform the patent granting without a patent attorney) – in practice, however, a patenting process implies so much special knowledge and pitfalls, that it always makes sense to ask for the assistance of a patent attorney.

The official fees depend essentially on the patent office, which charges for the search and the examination of the patent application. The German Patent and Trademark Office charges about € 500 in fees until the patent is granted, and the European Patent Office charges about € 4,000 of which approximately € 1.500 are incurred at the beginning of the search and the remaining in the following years.

The patent attorney’s fees depend primarily on the effort that your patent attorney is investing in the preparation of the application and further process. Most patent attorneys have an hourly rate ranging from € 250 to € 450. Often, lump sums are also agreed for the initial preparation of an application, which may be approximately in the range of € 3,000 to € 15,000. These prices are very difficult to compare and mostly reflect how much effort the patent attorney invests in the preparation of the application, which can lead to a varying degree of detail of the application.

Furthermore, one has to expect that until the completion of the examination process, further legal fees in the amount of several thousand euros are necessary – but this can vary greatly and depends on various factors, for example: how many answers to office actions are necessary and how complex they are. A very rough estimate here would be that the legal fees incurred in the course of the examination process are approximately € 5,000 (which can vary widely).

All in all, you roughly have to expect a investment of € 10,000 to € 20,000 in a patent grant procedure.

Does it make sense for me to apply for a patent?

Ultimately, this is an economic question that the inventor or entrepreneur can only answer for themselves. But we can give some help for this, which is based on our extended experience in this field.

As shown, a patent application represents a substantial investment. This is usually worthwhile only if there is a substantial economic interest involved. Our rule of thumb is: If you were now willing make a downpayment of € 100,000, so that your invention will not be used by anyone else, it is worth making a patent application. If you were now not willing to make a downpayment of € 20,000 for that, you have to question very carefully whether the investment makes sense – in between these two values, there is a certain gray area.

In evaluating this investment, there may also be other aspects playing a role alongside the legal advantage of exclusive rights – for example, the advertising effect of a patent and also the effect that a patent could have on potential investors.

All of these aspects should be considered in the decision-making process of whether a patent application makes sense for you.

Do you have more questions?

We hope that we have been able to answer your initial questions. Let us know if you have any further questions or would like advice on a specific invention! You can reach us at mail@stellbrink-partner.com or by phone at + 49-89-41112880.

The basic rationale is the following: There are some patents protecting a technological standard, e.g., a patent that is essential for a mobile communication standard. That is, anyone using this mobile communication network has to make use of this patent. Such patents would grant the patentee a disproportional amount of power if the patentee could exclude any other party from using this patent. This is why the patentee is obliged to grant a FRAND license to any party willing to accept such a license. In particular, the patentee of a standard-essential patent cannot successfully assert a cease and desist claim in court if the other party is willing to accept a FRAND license.

The basic rationale is the following: There are some patents protecting a technological standard, e.g., a patent that is essential for a mobile communication standard. That is, anyone using this mobile communication network has to make use of this patent. Such patents would grant the patentee a disproportional amount of power if the patentee could exclude any other party from using this patent. This is why the patentee is obliged to grant a FRAND license to any party willing to accept such a license. In particular, the patentee of a standard-essential patent cannot successfully assert a cease and desist claim in court if the other party is willing to accept a FRAND license. The unitary patent has been in the works for a number of years. The basic idea is simple: allow for a central system of patent litigation for patents in Europe (as opposed to litigation being tied to each of the individual countries where a European patent is validated). Based on the agreed rules, a new court would be established having a central division in Paris, London, and Munich.

The unitary patent has been in the works for a number of years. The basic idea is simple: allow for a central system of patent litigation for patents in Europe (as opposed to litigation being tied to each of the individual countries where a European patent is validated). Based on the agreed rules, a new court would be established having a central division in Paris, London, and Munich.